Home can

have multiple meanings for migrants. It can indicate the house they are living

in, the town they grew up, the country their family are residing and the

non-physical space for social relationships. It is significant yet problematic

at the same time, especially for Chinese migrants. From a Chinese linguistic

perspective, “home” and “family” are the same thing, they are all written as “家 (jia)” in Chinese. This might

explain the inseparable rapport between the social relation and geographical of

home in traditional Chinese culture. Home used to be the centre for Chinese

families, where traditions and rituals were passed from generation to

generation. However, in a world of mobility, migration has become a common

theme in Chinese diasporas, and the big family clan shrinks inevitably.

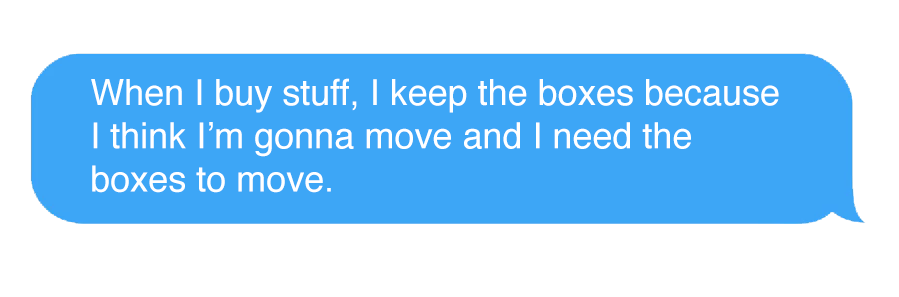

![]() This is a dialogue about homes between me and my interviewees from Chinese diasporas

This is a dialogue about homes between me and my interviewees from Chinese diasporas

How do you see home?

In the age of globalised migration, home is never still and centre to human’s life. It is temporal rather than spatial, and imaginary rather than physical. As a transnational traveller, I always wonder what is that invisible hand that displaces us somewhere geographically but elsewhere emotionally? On our journey from here to there is the endless exploration in the in-between area of uncertainties.

We can never forget our first time landing at

the Heathrow Airport. After a long fourteen hours transnational flight, we

finally arrived at the border control, jet-lagged and exhausted.

There was a long queue in front of the small desk behind the security windows. Woman with a hijab, a young man with a full rucksack, and a big family with kids running around, we all waited anxiously for inquiry and document check whilst the fast track on the other side seemed empty. Some people walked past the fast track quickly, leaving the other side frustrated. The airport is a centre for control and power. When people from other countries flock here, they will soon be confronted by the first frontier of nations.

While the arrival side is tense and crowded, the departure side is blowing a dazzling bubble of postmodernity. The big screens keep rolling advertisements for bank investment or luxury commodities. Walking along the hallway with bright artificial light, you can purchase the latest fashion couture or order a glass of Brut in a restaurant. In a sudden daze, you can’t distinguish which country you are in except for the Big Ben souvenirs that look the same in every store. The departure time is ticking while you forget the time of history. The history becomes the imagination and interpretation printed on travel pamphlets. We will sit on the bench and imagine the other side of the world, whilst none of the thought is real. Will travellers find a moment of rest within here? I’m seeking answers. There was one year, wherein I took 18 flights, so many flights that I no longer felt excited at layers of clouds against the blue-washed sky outside the portholes. I had always been intrigued by airports when I was a kid, it used to be a theme park for me. What has been left now is only a relentless transfer hub where we envision a future nostalgically.

The airport is bright, airy, busy, and warm as spring. It is physically located on the map while not belonging to any place. Travellers from all over the world have a moment in their life to meet others, shortly afterward, they become the particles in the accelerator, being thrown to the sky, on the journey to a new life whether we are prepared or not.

、

There was a long queue in front of the small desk behind the security windows. Woman with a hijab, a young man with a full rucksack, and a big family with kids running around, we all waited anxiously for inquiry and document check whilst the fast track on the other side seemed empty. Some people walked past the fast track quickly, leaving the other side frustrated. The airport is a centre for control and power. When people from other countries flock here, they will soon be confronted by the first frontier of nations.

While the arrival side is tense and crowded, the departure side is blowing a dazzling bubble of postmodernity. The big screens keep rolling advertisements for bank investment or luxury commodities. Walking along the hallway with bright artificial light, you can purchase the latest fashion couture or order a glass of Brut in a restaurant. In a sudden daze, you can’t distinguish which country you are in except for the Big Ben souvenirs that look the same in every store. The departure time is ticking while you forget the time of history. The history becomes the imagination and interpretation printed on travel pamphlets. We will sit on the bench and imagine the other side of the world, whilst none of the thought is real. Will travellers find a moment of rest within here? I’m seeking answers. There was one year, wherein I took 18 flights, so many flights that I no longer felt excited at layers of clouds against the blue-washed sky outside the portholes. I had always been intrigued by airports when I was a kid, it used to be a theme park for me. What has been left now is only a relentless transfer hub where we envision a future nostalgically.

The airport is bright, airy, busy, and warm as spring. It is physically located on the map while not belonging to any place. Travellers from all over the world have a moment in their life to meet others, shortly afterward, they become the particles in the accelerator, being thrown to the sky, on the journey to a new life whether we are prepared or not.

In many cases, people choose to migrate because they want to go somewhere better. It seems a better life is always waiting for them at one of the next exits. At the same time, migrants love to examine themselves upon the past. Some people stubbornly keep old rituals and some frequently recall memories. Some migrants might discard a certain culture when they were young, but they often come back later at some point in their life. Cultural identity seems like a marketing tagline on social media today. It is a public sphere. We are allowed to brand ourselves with where we came from, but we are not expected to reject it. We have to be so sure, or else we are rootless.

It is like McLuhan’s famous quote “We look at the present through a rear-view mirror. We march backward into the future.” Migration is a driveway, cars with passengers are always in transit. Are people in the car looking back or forward? Do they actually know about the stops they passed by, if not only from representations on billboards?

How do memories shape our perceptions of homes?

My dad was born in the water. My grandma gave birth in a lake when she was cutting water plants. It was a day in July, but my dad never figured out the exact birth date. His father was a boatman, and the whole family lived on the water, the small branch of Yangtze River. They earned a living from fishing, transporting livestock and villagers. Time for them was only a rough scale of sunrise and sunset.

In later years, the family moved ashore, because my grandad found a job as a Chinese painting teacher in a middle school. In fact, I would never have known this history if not for this research, since my dad never looked back. I always thought my grandad could only stand still and paint. I remembered when I was very young as a kid, my grandparents moved to the city, because the village was gone from urbanisation. I spent several summers in their house, where he would teach me Chinese Gongbi drawings. Grandad repetitively drew sailboats, reeds, herons and lotus flowers. I didn’t like it then and always asked him to draw cartoon characters for me. But now when I recall this, I realise maybe the water means something special for him, it might have always haunted him (and probably everyone in the family), although nobody talked about it. I’ve never been close to him, because he always grumbled that I was so disobedient and stubborn as a mule, same as my dad. It seems they never really communicate. Despite my grandad paints and draws, weirdly, none of the family, except for me, ever touches the paintbrush. Even for me, I was forced to study scientific majors in college regardless of the fact that I loved to draw. Sometimes, I feel that there are these rebels between each generation, my dad rebelled against his parents by not studying arts and me rebelled against my parents by not studying sciences.

He is very old now, in recent years, he spent most of his time writing up a family clan genealogy. He was so obsessed that he even asked craftsmen to make this exquisite miniature wooden temple for the genealogy book inhabiting inside. In my last visit to him two years ago, he showed me the book and pointed out my original name densely surrounded by other unheard names. I couldn’t imagine how he traced back to all the relatives and ancestors since they actually lived on the water, floating around, especially when the old village was gone. It seems very apparent to me that the heritage of the big family matters to him so much, and only matters to him, no one else seems bothered.

On my visit that day, another unforgettable event happened. He handed me an iron box carefully and seriously in front of the family. It was an old A3 sized tea box filled with Chinese painting books from the 70s to 90s. He said to me that he is too old to hold a paintbrush now, and I’m the only person who inherited his art blood in the family, so he wanted to pass his collections to me. I thanked him, feeling the box unspeakably heavy. An idea of family heritage just flitted through my mind. I had never thought about family heritage, and I had always struggled to locate my home spiritually and physically. Yet in that very moment, I sensed the bonding of the family and cultural spirits that trans passed generations.

As a home on a boat that drifted on rivers and lakes, the water witnessed all the family events from birth to death. Somehow, this family memory is deteriorating and decaying as no one dwelled in the past. It seems that everyone wants to forget. My dad changed his given name and only remained the family name when he went to university, and ironically, I discarded both my first name and surname that had been called for 15 years when I went to a different school. It seems rather odd that the whole family is in an extreme binary of remembering and forgetting. We act in an absolute forgetfulness or else absolute reminiscence. Two years ago, I attempted to trace back the family home geographically, but when I arrived there under guidance of GPS, only did I find new avenues being built around for tourism. Even the city is forgetting.

Trinh-T Minh-ha discussed this concept of remembering and forgetting in her essay film Forgetting Vietnam (2015). She noted, “To really forget, we must fully know what we want to forget”, there is always remembering in forgetting. They are non-binary and inseparable. To forget what is remembered, and to remember through the act of forgetting. If in Minh-ha’s film, people are acting the forgetfulness of wars, then for my dad’s family, maybe they are forgetting the previous hardships contextualised in society and historical moments. But the problem is what I am forgetting, especially when I am removed from that history and I don’t have anything to remember. And weirdly, why do I sense the belonging of home from a remoteness-in-time and fragmented narratives through the eyes of others. Ganguly (1992, pp. 29-30, cited in Rapport and Dawson, 1998) argued, “the stories people tell about their pasts have more to do with the continuing shoring up of self-understanding than with historical ‘truths'”. I didn’t experience any of that history, they are just representations and interpretations for me, but somehow they become the site where I can envision and rationalise my cultural identity.

For today’s emigrants, It is increasingly difficult to have a figurative and truthful image of the past. They are no longer like trees that can be easily and clearly located from the origin to the end. They are like water flowing in the cycling system. Sometimes they are rains, sometimes they are rivers, and sometimes they are the oceans. It is all fluid and constantly moving with no definite end. If in the past, when people ask where you are from, emigrants can clearly name the geographical place, today, the weight of location has been mitigated. Relatively, social relations become more crucial. When social relations are disrupted, we can only congeal history into representations for identity cultivation. The lifelong individual is just a fleeting moment in the water cycle, perhaps part of the river or part of the sea. Only the events carried along such as fallen leaves or small pebbles can tell where you are and where you are from. Some of them can be brought to the next journey, to the next generation, elsewise they might get eroded and disappear.

Memories often come through someone else’s eyes such as history or family heritage.

My homeland attachment comes from a story told by my dad on his birth in the water. My grandma gave birth to him in a lake when she was cutting water plants. His whole family lived on a sailboat, roving about the small branches of the Yangtze River. I’m never a nationalist, but I sense a strong emotional connection to the Yangtze River, as it bred the civilization, the Chinese people, and my family. Although none of these memories I actually lived, neither did my dad, he was told by his parents.

“To really forget, we must fully know what we want to forget” (Film, Forgetting Vietnam, 2015), there is always remembering in forgetting. What we remember is essentially illusory, and what we forget can never be forgotten.

These family memories are cast as my emotional belonging, whereas I can never locate in real life.

Homes on digital devices

Eating has always been a cultural thing for Chinese ethnic people. Family used to gather around in Chinese New Year for big meals. What people eat usually follow the local traditions, such as dumplings or fish. They are symbolically meaningful as the traditional concept of home. I haven’t had Chinese New Year gatherings for years, but I always got a video call from family members, through the 5-inch screen, I could see them having dinner while me holding a bowl of breakfast cereal. Digital communications successfully sustain my proximity to the family, however, it seems that the traditions and rituals have become the spectacles. They attract me as the exotic image from a remoteness of time, instead of being actually lived.

Journey map of interviewees’ migration

“Our present age is one of exile”, says Minh-ha. In migration and banishment, we fill the suitcase in a hurry with passports, documents, bank cards and clothes. Will the homogenised belongings tell the personal story of the emigration? If not, who has the power to tell and document the privatised life story of an emigrant?

In the 8th century, Chinese poet He Zhizhang wrote two poems all named in Hui Xiang Ou Shu after he resigned from the government and returned to his hometown. In the first one, he wrote how he spoke the same dialect but was seen as a stranger by the local kids. In the other one, he lamented how people and things changed in his hometown: only the mirror-like lake in front of his house remained the same, invariably rippled and waved by the spring breeze. For migrants in the past, they could find a sense of control from still landscapes, however, for the migrants today, how can they locate themselves in the rapidly changing landscape?

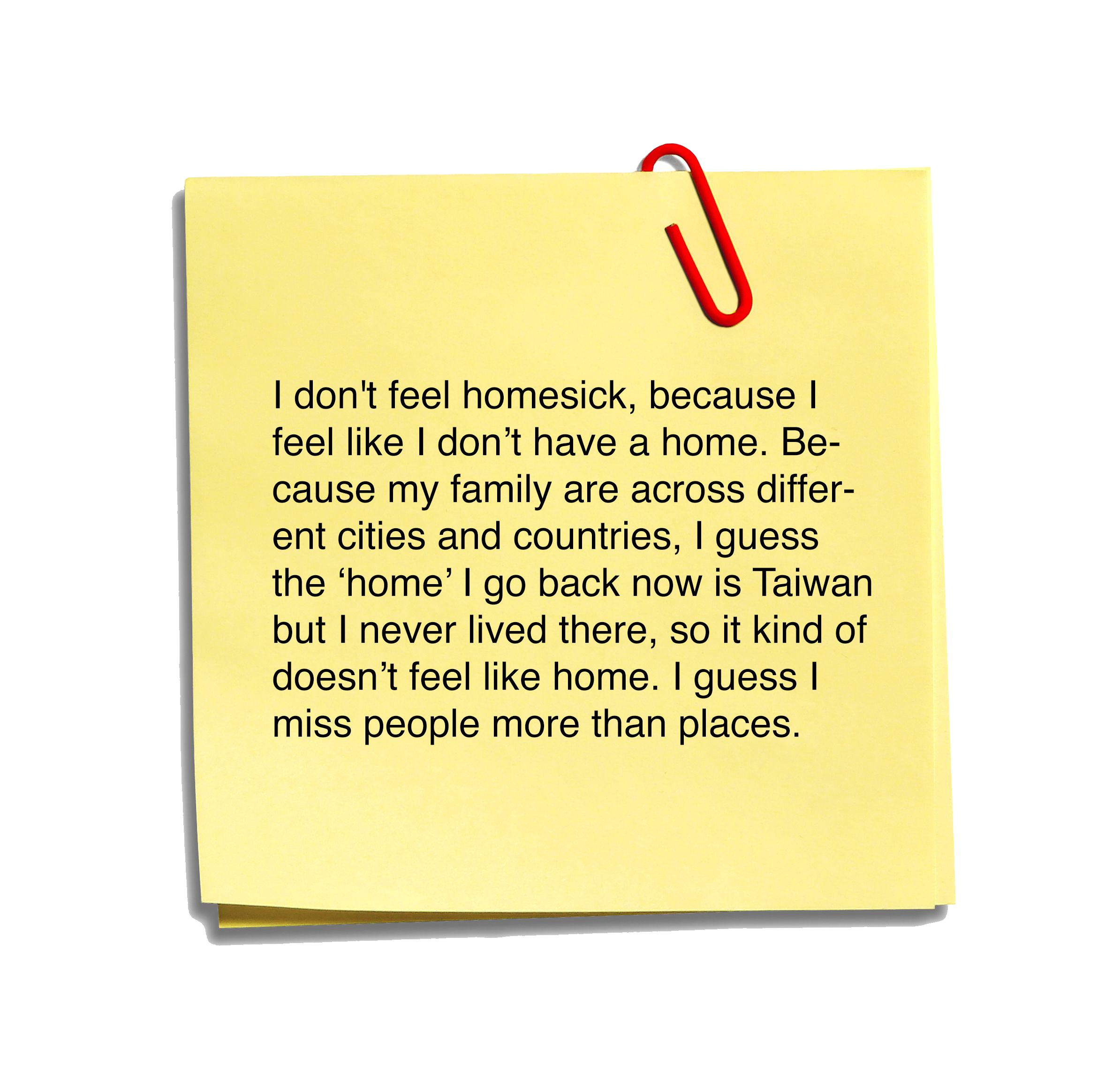

Archiving Life in a box